1.

[The day before white tantric: one 62-minute meditation]

SA-TA-NA-MA over and over again for 62 minutes. The chant hijacks my voice about halfway in. My mouth goes on chanting, sounding it out, without my conscious participation. I lift up through the sound to where it gathers overhead. All the voices make an invisible vibrating cloud, a sound soul that is ageless: no beginning and no end. All the bodies in the tent are but aspects of it. Sometimes, our voices join in unison. Sometimes, they alternate in call and response; a seemingly ancient phenomenon that occurs, too, in nature: with birdsong, with the rising and fallings of the tides, with light’s response to darkness when, each 24 hours, we rise again and again at daybreak. The sound ends and the cloud settles until I’m again behind my eyes, on my back, my hand touching the hand of the woman at my side. Every cell in my body seems to vibrate. I am the freshly plucked string of a well-tuned instrument.

2.

[The day of white tantric: 6 separate meditations]

“The masculine energy faces the basketball courts. The feminine energy faces the lake.” The facilitator speaks these words into the microphone, quieting the crowd of hundreds of people dressed in white. I simultaneously admire her for using inclusive language and wonder at the word choice, as though I could break myself in two, separating yin from yang in two balls of energy to face two different directions. The crowd is organized into several neat lines of couples facing one another, shoulder-to-shoulder with other couples. There are white tantric yoga rules: if you need to get up, raise your hand so a monitor can come sit in for you to fill the space; if you do get up, do not cross the lines; don’t get up if at all possible; don’t look around. The precise geometry of the bodies in lines is of the strictest importance. My partner, also my beloved, says, “I want to be the masculine energy,” with a bit of a child-like whine. I laugh and agree thinking yes, for once, I can be the woman. Somehow, I end up being the masculine energy anyway, both of us having misheard the instructions.

“Raise your hand if your partner isn’t back,” says the facilitator. My new friend, sitting diagonal to me on the opposite side of the couple to my left looks at me with wide eyes and says, “raise your hand if your partner isn’t black?” (She’s one of the few brown faces in a sea of white people.)

I laugh loud, appreciating her quick wit: so much subtext in one small joke. She smiles humbly. “I love her,” she says to my girlfriend, “she laughs at all my jokes.”

I’m seated on my new, very expensive meditation cushion that I purchased from the on-site vendor who hand-made it with buckwheat and hemp then brought it to the yoga festival to price gouge unprepared bourgeois yogis (like myself) who paid hundreds of dollars to spend a week deprived of all creature comforts and be subjected to excruciating meditation poses for unspeakable durations. One half of my mind is anticipating the magic I’ve been promised from this practice of white tantric yoga and one half is already dismissing it as ridiculous and the last laugh of a big joke that a man from India decided to play on all the spiritually starved westerners he encountered after moving to the States in the 70s. Nevertheless, I’m perched on my meditation pillow, ready for whatever happens next.

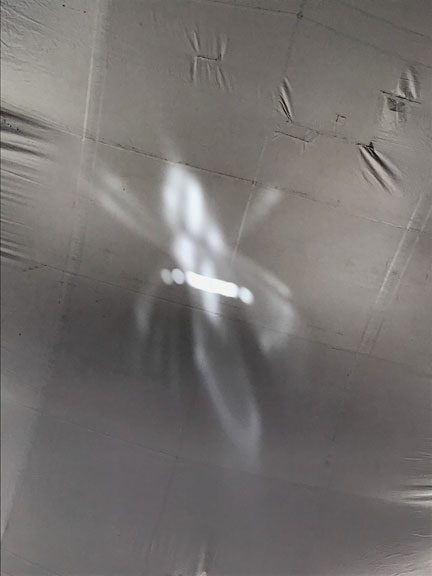

And what happens next is brutality: holding my arms up parallel to the ground with my left hand wrapped around my right fist for 62 minutes while staring at my thumb, which sticks straight up. My arms begin to burn and shake after a few short minutes and I bring my knees up to prop them; a cheat I see other people doing in my periphery. I get to know the back of my thumb and its network of fine creases very well as I keep my gaze fixed on it, the blurred face of my beloved floating behind doubled, sometimes tripled. For most of the time, I hold my arms up without the support of my knees and feel an intense pain in the center of my back that feels exactly like the puncture of a small knife. I experiment with small adjustments to my posture to see what it does for the pain, if it lessens or intensifies or disperses it. Eventually, I get too distracted by my thumb and its creases to even notice the pain anymore, seeing the skin cells individually, the mitochondria in the center of each one, the DNA coiled inside, the code handed down through generations to dictate the details of my appearance, my speech, my preferences, even. Around the DNA and inside the cells and around the cells is space. Indeed, my body is more space than matter, and this is where I disappear. The body and its pain and its eyes and its thumb all dissolve leaving only the space. I see my beloved across from me and wonder how it’s possible to still see her with no eyes. Her face is still a blur, just like it was when the thumb was in focus, but now there is no thumb and no focus. The blurriness of her face emphasizes the shapes of her mouth and eyes, curved lines and sparkles. As soon as I make a judgment, that these shapes are beautiful, that’s when the body and its pain and thumb all come back. I get through it to the end. When I lay down, relief filling me like helium, I stare at the ceiling of the tent and wonder if I’m actually floating toward it or if it’s a hallucination. There, on the ceiling, the light makes the pattern of an angel with four butterfly wings.

3.

Another 62 minutes even more brutal than the first with spent arms held aloft and hands around eyes like binoculars, thumbs pressing closed the nose at the top of the breath. “The important part,” says the facilitator, “is to synchronize your breath, not to hold up your elbows. You can relax your elbows.” At this, we both bring up our knees to prop our arms and ease the burning knots of tension they’ve become. Only this time, it offers little relief. My back and arms still burn to almost the same intensity. I fix my gaze on the brown freckle in her left eye shaped like a tiny leaf sitting vertical over the pupil, violating the oval of pale, mottled green-gray behind it. We both struggle through every one of the 62 minutes of this meditation, softly complaining periodically throughout, irritating our fastidious neighbors to the right. For the most part, we do synchronize the breath, so that at times, it seems we share one set of lungs.

4.

Yes, 62 minutes but mercifully, arms can rest down while the hands make an opening and closing motion, joined at the fingertips. We stare in each other’s eyes and chant “wahe guru” over and over. After the first two, this one feels blessedly easy, and I melt into the rhythm of the chant and the motion in time with my partner, again staring at the small brown leaf in her eye, becoming entranced through it all. When it’s over, we break for lunch. I walk around feeling only half my weight, like I might lift off the earth with each step. It’s a feeling similar to what I’ve felt in the past from marijuana or alcohol, only sharper and cleaner. “Am I still sober? Or did I relapse?” I joke, and she laughs. She repeats my joke to all the yogis we talk to and they smile knowingly. We remove our shoes and wade into the lake. Its chill is bracing and somewhat grounding. I notice the green moss wavering on the bottom, the schools of minnows moving away from us. I squint at the bright sky and notice all my senses are heightened. The sweet drunkenness from the meditations makes me want more, despite the pain.

5.

The first of three segments of the afternoon ends up being the most physically challenging of them all. The posture: sit with both arms extended out and up at a 60-degree angle for 62 minutes. There is no way— No. Way.—that I will be able to hold my arms up for that length of time. The vocals are split into three parts: for the first twenty minutes or so, we are to whistle along to the chant and lock eyes. For the second, whisper along, eyes still locked. And for the third, close the eyes and be silent, listening only. The first 20 minutes prove too painful and effortful to comply with the whistling. I labor to keep my arms up, both shoulders screaming, my mind insisting that it isn’t possible. I listen to the mantra and count out one verse of it, which lasts about eighteen seconds. I hold my arms up for four verses then bring them higher over my head, letting the first two fingers of each hand hook together and hang there. It’s a way to rest without bringing my arms down, I reason. And after four verses in this position, it hurt just as much, so I rest from it by bringing my arms back out to 60 degrees. This trick allows me to keep my arms up for the whole of the first twenty minutes and the second twenty minutes, to the surprise of my partner, who intermittently, unabashedly, rests. Somewhere in the second twenty minutes, her eyes turn red around the rims, her lips tremble, and tears spill down her cheeks. I feel her emotional pain in my own body and I see what she sees: the image of her dying father. I know it’s another wave of grief she’s feeling and I feel it with her; bear it on my wings, which are flying me across a landscape of memories, both hers and mine. By the third twenty minutes, when it’s time to go silent and close our eyes, I fly over a memory from when I was nineteen years old and adopted a puppy. She was small enough to fit curled in the palm of my hand, too small to scale a single step in the flight of stairs up to the apartment I shared with my older brother, the one who I haven’t seen or heard from in more than four years. I remember how he named our new puppy Perry, which I liked for the way it bent her gender, and how he loved her and played with her endlessly each day at a time when I was too unavailable in my active alcoholism to properly care for a pet. He would run through the long, narrow apartment and she would chase him and he would yell, “Why are we running?” He would throw the ball thousands of times for her to leap after and return, turning a terrier into a retriever. Then I think of how he disowned our whole family, cutting us off from him and his two children, my niece and nephew. And I dwell there in that grief and pain and I cry. I weep unselfconsciously, my arms held up now of their own will, as though the rest of my body were hanging from them. The tears eventually subside and my heart opens wide to my brother, wherever he might be in the world, and I offer him unconditional love and forgiveness. When it’s over, I marvel at the fact that I did not bring my arms down even once for the entire 62 minutes. We walk outside and lie on the grass during the break. Above me, everywhere, are flitting tiny points of light like luminescent molecules. “Do you see the fairies?” I ask, “they’re everywhere!”

“Oh yeah, I see them, like little dancing molecules,” she says. I’m too exhausted and too high to be surprised. I expect them to poof and disappear, aware that I’m hallucinating or else being offered a brief glimpse into another dimension and that the door will soon slam closed. But they persist, even when I lift my hands into them. They swarm around my fingers. I laugh and sweep them into me, toward my heart. “Stay with me, little fairies,” I say, my giggly voice like tiny bells in my ears.

6.

The next meditation is a short 31 minutes and it consists of an almost aerobic movement of the arms, stacked at the forearms, rapidly up and down, touching the forehead each time, chanting wahe guru. I find its rhythm is sustaining and although I’m tired and sore and sweating in the hot tent dense with bodies and breath, I keep up. At one point, my partner makes a funny face and I laugh uncontrollably. I see our faces as if from above, both contorted into red smiles. I slide back into my sore, sweaty body and forgive myself, finally, everything. Swipe it all clean in one swift ascent/descent. Like karmic windshield wipers, as though there was unlimited power in my overlapping forearms, unlimited opportunities to wipe my flawed history clean, one every moment, in fact. To see myself and know I was wrong and love myself still. And my arms lift to cover my eyes and lower to reveal again my partner’s shining smile charged with joy. And everything is forgiven. Every single thing. And it is just that sudden.

7.

The final meditation is the second hardest of the day, almost as hard as both arms held up for 62 minutes. This time, it’s just the right arm held up with the left palm over the heart center and the right fingertips touching in sequence while chanting SA-TA-NA-MA. I become aware in the midst of it that I have come full circle: It’s the same chant that we did for the first 62-minute meditation the day before. The arm stays up for approximately 80 percent of the time as I gave it occasional, brief, intoxicating breaks by bringing it down and propping it on my knee. There are lapses of hallucinogenic states, including one in which I’m a constellation of stars, birthing new suns for solar systems between my fingers as they touch. The suns spin away, collecting a system of planets to hold orbit around it, each of the planets springing forth its own breed of life. Then there’s one in which my partner’s face turns into a horizon where the clouds are the color of the water, making the sky indistinct against the lake’s surface. I chant harder, louder, keeping my eyes trained on that blurred line, the line between reality and fantasy, how once this woman was the object of my fleeting fantasy, the fantasy of us kissing in many different places (lying in bed, against a wall, on a couch, in a car), but at that time she was as unattainable as the moon, and now here we are. Water and sky, liquid and air, fantasy and reality: they have the same molecular structure. One is merely less dense. And so it is that I have distilled her from my fantasy into my reality. The catalyst was, of course, a story, the long version, which she listened to like she listened to a thousand of my stories before. Only this time it was about her and the quality of my desire. From the foundation of our deep friendship, I stepped easily over the threshold into more. Into this: what sits in front of me today, chanting, holding up her arms, the reflection of that which I have come to be, to know myself as, or the complimentary puzzle piece designed to bring balance, or the long lost half of my soul mysteriously emerged from the past, from deep under the surface of the water, from a place buried. Long buried under layers of lifetimes, once gone but now risen again to the surface and up, against our wildest expectations, claiming the sky, ridiculing the line separating fantasy from reality, making a mockery of it. After, I lie down again and feel a peace rise up within me. I’ve travelled far to places on this earth in repeated attempts to find this peace. As though it wasn’t right here inside me. All mine. All along.

Recent Comments